In a career that spanned more than six decades of creative activity Joan Miró developed a formal idiom that transformed twentieth-century art. In painting, drawing, sculpture, ceramics, tapestry and printmaking Miró explored the language of signs, aligning his project with the Cubists’ interest in the structure of representation and the Surrealists’ investigation of writing and poetry. Conceiving his work as peinture-poésie (painting-poetry), the Catalan artist forged a language-based aesthetics whose legacy influenced an entire generation of postwar artists in Europe and America.

Born in Barcelona on April 23, 1893 Miró came of age at a time of major social transformations in his native Catalonia. A member of the first generation of artists and intellectuals for whom the Catalan language was the instrument of national consciousness, Miró felt more at home in the company of writers and poets than painters. From his early participation in the Catalan literary avant-gardes during World War One, to his engagement with the poets and painters of the Rue Blomet in Paris, and shortly thereafter with the nascent Surrealist movement, Miró’s visual work was informed by his abiding interest in the language of signs and in the relations between images and texts.

As early as 1918 Miró spoke of the “calligraphy” of a tree or a rooftop, which he described “leaf by leaf, twig by twig, blade of grass by blade of grass, tile by tile.” Taking inventory of the world around him, Miró began to reduce objects to basic contours and essential elements. This process of reduction and simplification purged Miró’s work of any vestiges of illusionism and shallow cubist space. He began to think of the surface of his supports as sites for inscriptions and marks rather than as windows onto the world. Reading would vie with looking in Miró’s practice. Eschewing non-objective painting as a dead end (in the mid-1930s Miró famously described the Paris-based group Abstraction-Création as an “empty house”), Miró turned to collage and to the world of objects to create complex signifying systems. His work in ceramics and sculpture put the reality of things under pressure, while his exploration of Japanese calligraphy in the 1960s tested the limits of signification. In fine-tuning and expanding his visual vocabulary, Miró developed a signature style that was entirely original, in the process inaugurating a new language for modern art. The eighty-five works by Miró in the Portuguese State Collection, spanning the years 1924–1981, allow us to chart this trajectory.

quepintamosenelmundo: art, contemporary art, art online, spanish art

PAN. Palazzo delle Arti Napoli. Via dei Mille, 60 (1,546.88 km). 80121 Nápoles

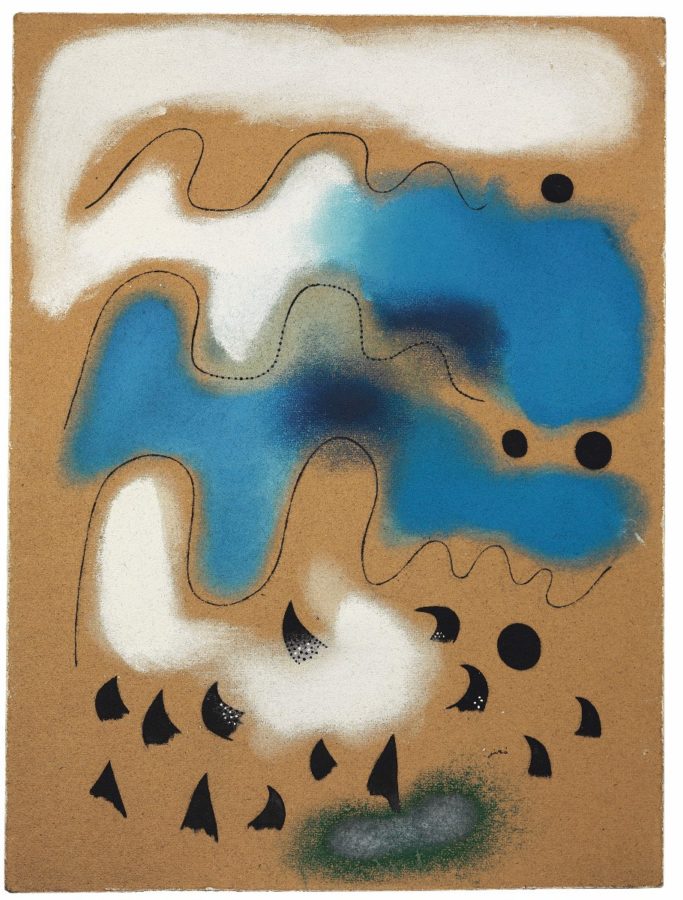

Image: Joan Miró “El canto de los pájaros en otoño” 1937